ST. LOUIS — Patricia Powers went a few years without health insurance and couldn’t afford regular doctor visits. So she had no idea cancerous tumors were silently growing in both of her breasts.

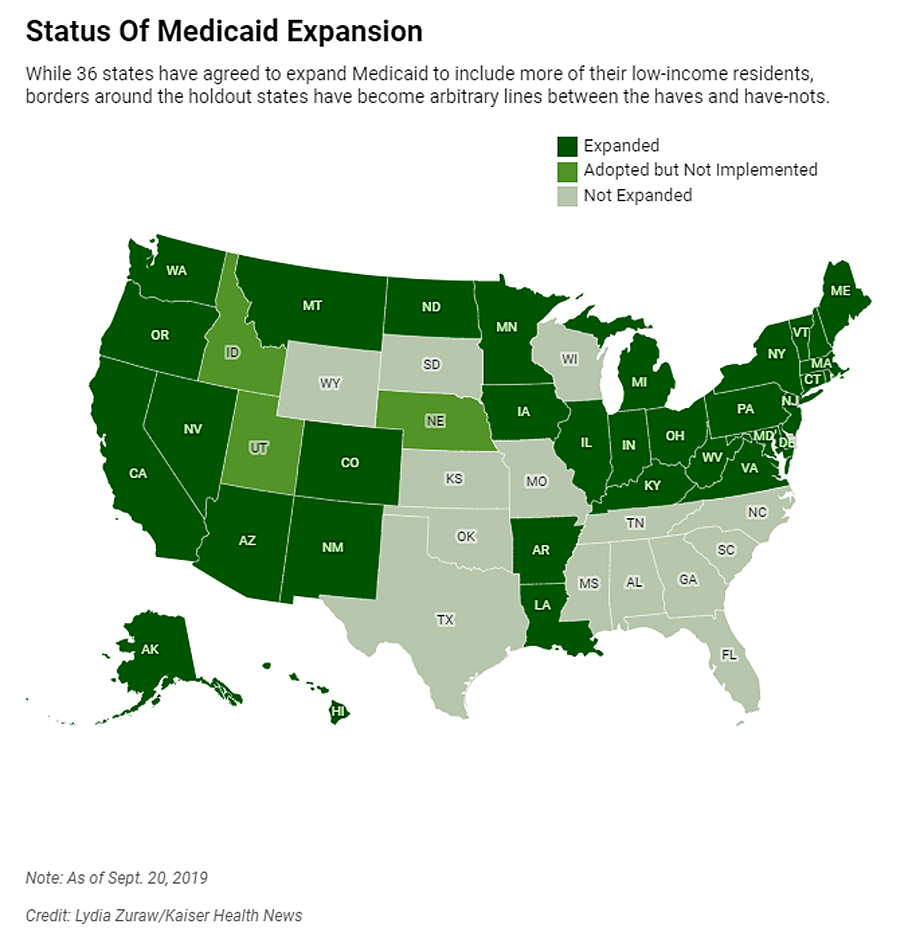

If Powers lived just across the Mississippi River in Illinois, she would have qualified for Medicaid, the federal-state health insurance program for low-income residents that 36 states and the District of Columbia decided to expand under the Affordable Care Act. But Missouri politicians chose not to expand it — a decision some groups are trying to reverse by getting signatures to put the option on the 2020 ballot.

Powers’ predicament reflects an odd twist in the way the health care law has played out: State borders have become arbitrary dividing lines between Medicaid’s haves and have-nots, with Americans in similar financial straits facing vastly different health care fortunes. This affects everything from whether diseases are caught early to whether people can stay well enough to work. (https://cliniclesalpes.com)

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. The ACA, passed in 2010, called for extending Medicaid to all Americans earning up to 138% of the federal poverty level, around $17,000 annually for an individual. But the U.S. Supreme Court in 2012 let states choose whether to expand Medicaid. Illinois did, bringing an additional 650,000-plus people onto its rolls. Missouri did not, and today about 200,000 of its residents are like Powers, stuck in this geographic gap.

Powers briefly thought about moving to another state, just to be able to get Medicaid. “You ask yourself: Where do you go? What do you do?” said Powers, who was in her early 60s when diagnosed. “Do I look at what’s happening in Illinois, right across the river?”

A recent University of Michigan study found Medicaid expansion substantially reduced mortality rates from 2014 to 2017. The researchers said Illinois averted 345 deaths annually while Missouri had 194 additional deaths each year. The same trends held for other side-by-side states such as Kentucky (did expand) and Tennessee (did not), New Mexico (did) and Texas (did not).

Dr. Karen Joynt Maddox, co-director of the Center for Health Economics and Policy at Washington University in St. Louis, said health care providers in her border city see how the coverage differences affect people. When treating Medicaid patients from Illinois, she said, doctors know procedures, equipment and medicines will likely be covered. With uninsured Missourians, they must consider whether patients can afford even follow-up medications after heart attacks.

Nonetheless, Medicaid expansion faces significant opposition in Missouri, a red state led by a Republican governor with GOP supermajorities in both legislative chambers.

Patrick Ishmael, director of government accountability for the Show-Me Institute, a Missouri free-market think tank, said offering Medicaid to people with incomes above the poverty level would drain resources from the state’s underserved poor and push up taxpayer costs. Though the federal government pays 90% of the cost of the expansion coverage, he said, Missourians contribute to that through their federal taxes. Medicaid already accounts for about a third of the state’s budget, which he said puts pressure on other priorities, like education.

“Missouri and other states need to think about whether they are a government that provides health care or a health care provider that sometimes governs,” he said.

Powers, a minister in the St. Louis suburb of Hazelwood, used to get health insurance through her husband’s job selling lumber and hardware. After he was disabled in 2009, their coverage continued on and off for a while, and her husband eventually received Medicare, the federal insurance program for seniors and people with disabilities. But Powers had no insurance starting in 2012 as the couple struggled on, at most, $1,500 a month.

Medicaid wasn’t an option for her. Missouri could have opened the program to more adults as early as 2010, in preparation for the health care law’s expanded coverage taking effect in 2014. Without the ACA’s expansion, adults who aren’t 65 or older or disabled don’t qualify, no matter how low their income. Missouri’s program generally covers only pregnant women and children from low-income families, parents with incomes about 22% of the federal poverty level and people who are poor and blind, disabled or 65 or older.

Powers and her husband earned too little for her to qualify for subsidies on the federal ACA marketplace, so she couldn’t afford to buy her own plan. And without insurance, Powers never saw doctors for routine health visits or screenings. She stopped taking her prescribed medications for high blood pressure and anxiety — until she could no longer do without her anti-anxiety medicine, Lexapro.

In early 2016, she discovered a place to get help when she gave her friend a ride to a St. Louis clinic for the uninsured called Casa de Salud, where health services cost less than $30.

Powers figured she’d ask about getting back onto Lexapro there. She got a thorough checkup. The doctor found a walnut-sized lump in her right breast, and a mammogram found a tumor the size of a grain of rice in her left. A clinic caseworker helped her sign up for a Medicaid program for breast cancer patients. She underwent surgery in April 2016, then had 35 radiation treatments and took follow-up medications.

She kept thinking she could have found the cancer earlier if only she had insurance. That would have meant less treatment and lower costs for taxpayers, who ended up footing the bill anyway. Research shows breast cancer in its earliest stage can cost half as much to treat as in later stages.

“Even if you didn’t care about the human cost, you should care about the economic cost,” said Jorge Riopedre, president and CEO of Casa de Salud. “Treating a disease at its first stage is always going to be much cheaper than treating it at its advanced stage.”

An Illinois Story

In neighboring Illinois, getting Medicaid through the expansion helped Matt Bednarowicz avoid debilitating medical debt after a motorcycle crash. He was able to go back to work after he was injured while delivering a package in mid-May 2018.

The wreck crushed his left foot, requiring doctors to insert pins in it. Without Medicaid, he would have faced thousands of dollars in medical bills.

“The debt would have been greater than I could comprehend overcoming,” said Bednarowicz, who is now 29.

His Medicaid kicked in “just in the nick of time” to cover the surgery, he said. It also allowed him to get psychiatric help for depression. More than a year later, he’s able to get around well — even jog — and works as a caretaker for an elderly man.

Having insurance helps people like Bednarowicz stay productive, said Riopedre.

“The person who gets sick can’t work, can’t support his or her family, can’t be a consumer and buy goods. If they’re not working, they can’t pay taxes,” Riopedre said. “It just is a tidal wave of downstream effects that if we can’t get it right, it’s going to have repercussions across the nation.”

Amid Controversy, Future Uncertain For Missouri

As the ballot measure push continues, Missouri Gov. Mike Parson, a Republican, recently created a task force to look into expanding Medicaid through a waiver allowing states to skip some federal requirements. His office referred questions to the state’s Department of Health and Senior Services, which in turn referred them to the Department of Social Services. Rebecca Woelfel, a spokeswoman for that agency, said the department doesn’t typically comment on potential ballot issues.

Ishmael, of the Show-Me Institute, said he hopes expansion doesn’t happen. He said the Medicaid system overall is wasteful, with outcomes often not fully justifying the expense. The cost of an expansion would depend on how it’s structured, he said, but “it could be a real budget-buster.”

The impact of an expansion on Missouri’s budget remains unclear. A February analysis by researchers at Washington University estimated it would be “approximately revenue-neutral.” But their estimates range widely for the first year depending on enrollment and other factors, from up to $95 million in savings for Missouri’s Medicaid program to costing $42 million more than not expanding.

Powers, whose husband died last year, said she fully supports Medicaid expansion.

But whatever happens, especially now that she’s suffering from heart failure, she’s grateful she won’t have to worry about being uninsured again. At 66, she’s now old enough for Medicare.

Comments are closed.