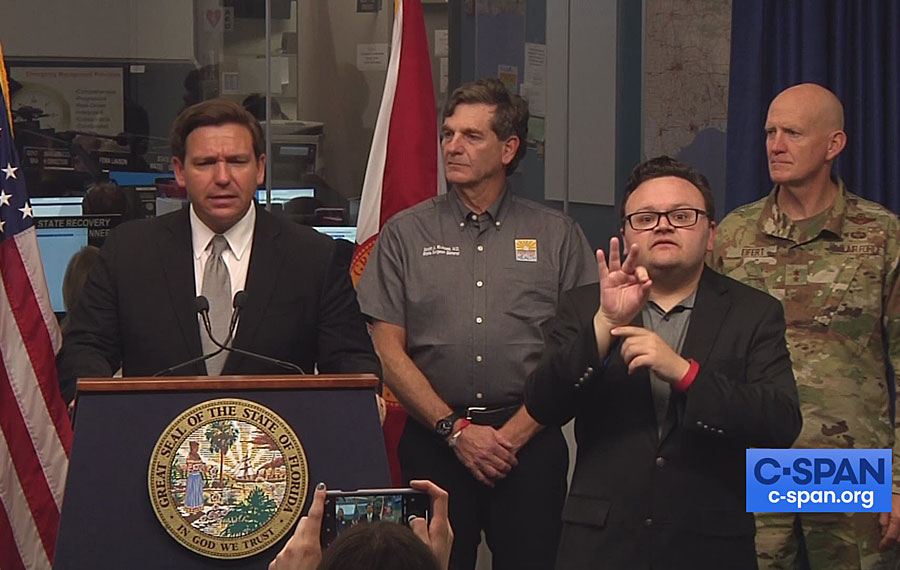

JUPITER, FL – Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has refused to issue a statewide “stay-at-home” order to stem the spread of the novel coronavirus because the disease has not hit many areas of the state, he said.

At least 30 states have issued statewide stay-at-home orders so far. Florida, among eight states with the most COVID-19 cases, is the only one without such an order.

DeSantis’ approach in trying to manage the disease without doing undue harm to the economy mirrors comments from President Donald Trump, who Monday reiterated his belief that a nationwide stay-at-home order is not needed.

“There are some parts of the country that are in far deeper trouble than others,” he told reporters. “There are other parts that, frankly, are not in trouble at all.”

But as the outbreak marches across the country, public health officials stress that the lack of testing is masking the true picture of the epidemic, a situation that they argue is playing out in Florida.

As of Tuesday night, 29 of Florida’s 67 counties had 10 or fewer cases of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. In 13 largely rural and poor counties — mostly in the northern part of the state between Gainesville and Tallahassee — no cases had been reported to the state health department.

Yet many rural counties have tested fewer than 75 patients in the past two weeks, according to health department data.

Public health experts and emergency management officials disagree on whether a statewide stay-at-home order would make a difference in these rural counties.

Several of Florida’s largest cities and counties — including all of South Florida, which has about 3,900 COVID-19 cases — have ordered people to stay at home. These orders generally make exceptions only for travel to grocery stores, pharmacies, gas stations or other essential errands. People are allowed outside their homes to walk or run but are not allowed to congregate in groups. They also exempt essential workers, including those in health care.

“I would be doing a stay-at-home order” across the state, said Dr. Leslie Beitsch, chairman of the behavioral sciences and social medicine department at Florida State University’s College of Medicine. “It tells people this is serious, and we are doing something unprecedented.”

But in Okeechobee County, an agricultural community with about 40,000 people in the south-central part of the state, Emergency Management Director Mitch Smeykal said, an order would have little benefit.

“The cows still have to be milked twice a day or they are not going to be able to produce any milk,” he said.

He said residents already understand the seriousness of the outbreak, having seen the run on food in area grocery stores and the early departure of thousands of part-time residents to return to their permanent homes.

As of Tuesday night, just 55 people have been tested in the county and no COVID-19 cases had been confirmed.

Smeykal said rural counties are likely not seeing anyone with the virus yet because people already live and work far from neighbors and crowds. But it’s only a matter of time until a positive test emerges, he said.

“We probably do have a case in the county, but it hasn’t presented itself yet,” he said. “We are not going to be spared from this.”

Florida has more than 6,700 cases of COVID-19 and has done about 65,000 tests — far fewer than the tallies in New York and other states. As of Tuesday night, more than 85 people had died and 850 had been hospitalized because of COVID-19 in Florida.

According to the Florida health department, only people who have had close contact with a laboratory-confirmed case of COVID-19 and have a fever, cough and/or shortness of breath can be tested.

On Monday, DeSantis issued a stay-at-home order for residents of South Florida until April 14, saying the action makes sense for the region because of the number of cases concentrated there.

DeSantis has ordered restaurant dining rooms and bars to close and restricted gatherings of more than 10 people across the state. The state has also closed all public schools. DeSantis directed travelers arriving in the state from the New York metro area or Louisiana to self-isolate for 14 days.

Dr. Marissa Levine, a professor of public health and family medicine at the University of South Florida in Tampa, said the paucity of positive test results in many Florida counties gives a false sense of security.

“Until we do more widespread community testing, we won’t really know who has been exposed,” Levine said. From her standpoint, she said, the governor should set restrictions across the state. “From a public health standpoint, there is no question that the earlier you do it the better.”

Florida’s large senior population, the age group hit hardest by COVID-19, is another reason to go to a statewide lockdown, Levine added. A stay-at-home order would signal to people, even in counties with few or no cases, that people need to change their normal behavior.

“When you don’t have such an order in place, I worry people may not be as cautious or [not] go about their hand-washing and social distancing,” Levine said.

In Hendry County, which has four positive COVID-19 cases after administering 63 tests, residents are practicing the same precautions as in urban areas on lockdown, said R.D. Williams, CEO of Hendry Regional Medical Center. The rural community halfway between West Palm Beach and Fort Myers reported its first positive test Sunday.

Williams said he favors DeSantis’ approach because projections on the spread of the outbreak in the region don’t support the need for a shelter-in-place approach statewide.

March and April mark the peak of the harvest season for sugar cane, so hundreds of migrant workers in Hendry County are still going to work.

“Those operations are going full speed,” Williams said. Because those workers are outside, he added, it’s easier for them to practice social distancing than in a production facility.

While rural Florida has not struggled with the coronavirus, if cases escalate, these areas could be hard-pressed to handle an outbreak because of a lack of doctors and hospitals, said Jerne Shapiro, a lecturer in the department of epidemiology at the University of Florida. Many rural residents also lack insurance and may not have a strong understanding of the health system or how to seek help, she said.

“This is going to exacerbate the problems we have in these rural counties where people now are struggling to get seen by a provider,” she noted. “The gap for this underserved population is only going to be magnified.”

Comments are closed.