LOS ANGELES, CA – Once upon a time a California 8th grader could have told you something about reapportionment – the first step in the vast undertaking known as redistricting. Of course, that is when Constitution tests were part of the curriculum, but the failure of the basic civics curriculum in this state is a conversation for School Choice. At present, though, the far more serious and largely looming issue, yet ironically largely oblivious to most voters, is that issue of redistricting.

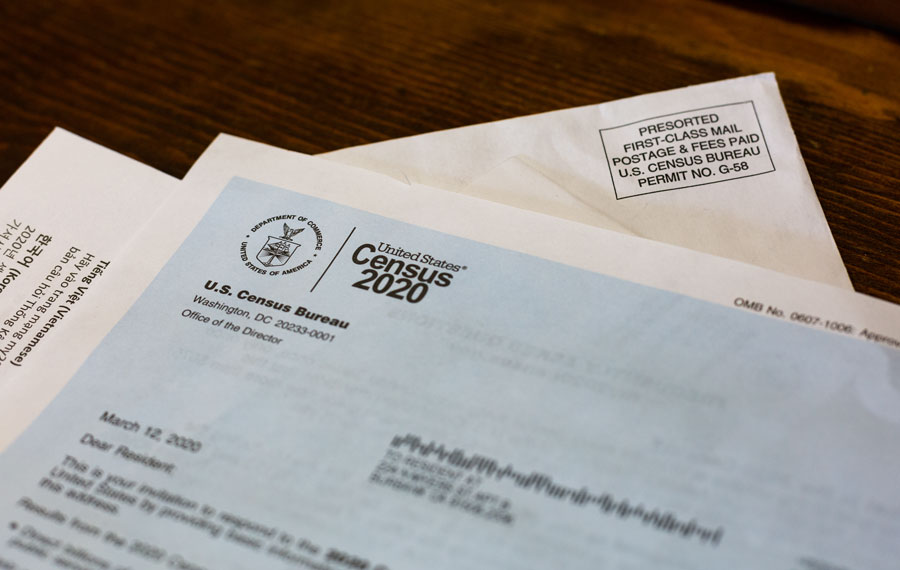

Redistricting is the process by which the lines are drawn to determine which constituents will be electing representatives to local, state, and congressional offices. This process takes place in all 50 states after the constitutionally required Census data for reapportionment is reported. At the state level, in California, this means lines have to be drawn for 80 state assembly seats, 40 state senate seats, 52 congressional seats (down one from 10 years ago), and 4 Board of Equalization districts. This process also plays out at county and city levels following different criteria.

Many states entrust this process to the state legislature, which essentially guarantees that the lines are drawn in favor of the party in control of the legislature at the time of redistricting. Others, including California opt for the increasingly popular option to utilize independent redistricting commissions.

Independent redistricting commissions are charged with (but not limited to only) ensuring compliance with the State Voter Rights Act, evaluating the populations, determining communities of interest, adhering to the directives issued to the commission upon formation, along with analyzing and taking into consideration public comments and input all in a delicate balancing act while delivering maps on time for the electoral process to proceed. It is a daunting and unenviable task. For the state of California, the task of redistricting is entrusted to 14 unelected, appointed commissioners – five Democrats, five Republicans, and four No Party Preference registrants.

In California, after the 2008 Proposition 11 vote, the independent Citizens Redistricting Commission was created in 2010. Now comes the real challenge. The commission is alleged to be independent. At the onset, during their first line drawing, there were the usual challenges and questions with the redistricting process, but it was generally accepted as better than a system without any pretense of impartiality. However, when the wheeling, dealing, and horse trading of the last redistricting cycle arrived at an independent commission for California, this was before the bully pulpit of social media was in its fully amplified effect. (youngmedicalspa.com)

Ten years later and “independent” commissioners are boldly defending their actions in the public sphere and in the midst of sharp media criticism are seeking public support to justify their decisions for what they claim to be “fair representation.” Yet, the seeking of voices to come to their defense is largely going to come from their audience of followers – followers of commissioners not known for impartiality, balance, or non-partisanship. Here lies the rub, and here lies the question of just how independent the independent redistricting commissions really are.

In a political climate as volatile as is the current temperament, it is naïve to suggest that “independent” commissioners are not bringing their own bias to the process. Whereas that can be more evident and easily followed in states where the legislature controls the process, with “independent” commissions and commissioners following the pathway of influence, history of deep partisanship, and the inescapable reciprocity of long-standing political relationships is often less transparent and much more circuitous. What this means for the invariable legal challenges that follow the redistricting process also is much less clear. While the courts are often the ultimate arbitrator, they usually are serving to act as check on the legislature. However, when the lines are drawn by commission, the refereeing of their actions can be perceived as less urgent, and risks delays on throwing the flag on the play as coming too late.

What that means for the pragmatic reality for representation of residents of our Congressional, State Senate, and Assembly districts is clear. If we are not much more actively involved in the process using our many voices to vociferously respond to the social media influence of those few commissioners in charge of this process, then our communities, the communities with whom we share interests, will be arbitrarily redefined by those who think they know better… and experience tells us they don’t. Let’s make sure we are heard!

Comments are closed.