TENNESSEE – With just a dozen days left in power, the Trump administration on Friday approved a radically different Medicaid financing system in Tennessee that for the first time would give the state broader authority in running the health insurance program for the poor in exchange for capping its annual federal funding.

The approval is a 10-year “experiment.” Instead of the open-ended federal funding that rises with higher enrollment and health costs, Tennessee will instead get an annual block grant. The approach has been pushed for decades by conservatives who say states too often chafe under strict federal guidelines about enrollment and coverage and can find ways to provide care more efficiently.

But under the agreement, Tennessee’s annual funding cap will increase if enrollment grows. What’s different is that unlike other states, federal Medicaid funding in Tennessee won’t automatically keep up with rising per -person Medicaid expenses.

The approval, however, faces an uncertain future because the incoming Biden administration is likely to oppose such a move. But to unravel it, officials would need to set up a review that includes a public hearing.

Meanwhile, the changes in Tennessee will take months to implement because they need final legislative approval, and state officials must negotiate quality of care targets with the administration.

TennCare, the state’s Medicaid program, said the block grant system would give it unprecedented flexibility to decide who is covered and what services it will pay for.

Under the agreement, TennCare will have a specified spending cap based on historical spending, inflation and predicted future enrollment changes. If the state can operate the program at a lower cost than the cap and maintain or improve quality, the state then shares in the savings.

Trump administration officials said the approach adds incentive for the state to save money, unlike the current system, in which increased state spending is matched with more federal dollars. If Medicaid enrollment grows, the state can secure additional federal funding. If enrollment drops, it will get less money.

“This groundbreaking waiver puts guardrails in place to ensure appropriate oversight and protections for beneficiaries, while also creating incentives for states to manage costs while holding them accountable for improving access, quality and health outcomes,” said Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. “It’s no exaggeration to say that this carefully crafted demonstration could be a national model moving forward.”

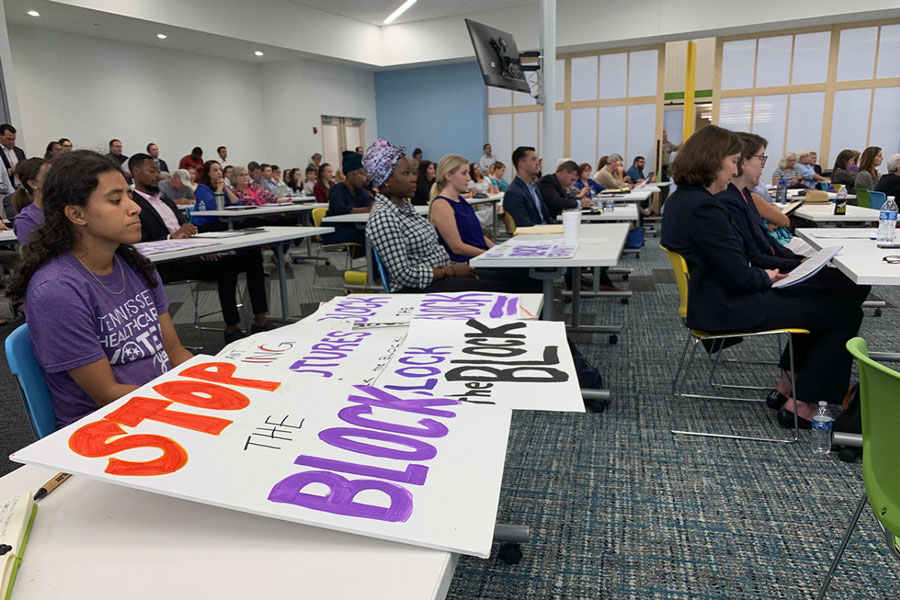

Opponents, including most advocates for low-income Americans, say the approach will threaten care for the 1.4 million people in TennCare, who include children, pregnant women and the disabled. Federal funding covers two-thirds of the cost of the program.

Michele Johnson, executive director of the Tennessee Justice Center, said the block grant approval is a step backward for the state’s Medicaid program.

“No other state has sought a block grant, and for good reason. It gives state officials a blank check and creates financial incentives to cut health care to vulnerable families,” she said.

The agreement is different from traditional block grants championed by conservatives since it allows Tennessee to get more federal funding to keep up with enrollment growth. In addition, while the state is given flexibility to increase benefits, it can’t cut them on its own.

Democrats have fought back block grant Medicaid proposals since the Reagan administration and most recently in 2018 as part of Republicans’ failed effort to repeal and replace major parts of the Affordable Care Act. Even some key Republicans opposed the idea because it would cut billions in funding to states, making it harder to help the poor.

Implementing block grants via an executive branch action rather than getting Congress to amend Medicaid law is also likely to be met with court challenges.

“This is an illegal move that could threaten access to health care for vulnerable people in the middle of a pandemic,” Rep. Frank Pallone (D-N.J.), chair of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, posted on his Twitter account. “I’m hopeful the Biden Administration will move quickly to rollback this harmful policy as soon as possible.”

The block grant approval comes as Medicaid enrollment is at its highest-ever level.

More than 76 million Americans are covered by the state-federal health program, a million more than when the Trump administration took charge in 2017. Enrollment has jumped by more than 5 million in the past year as the economy slumped with the pandemic.

Medicaid, part of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “Great Society” initiative of the 1960s, is an entitlement program in which the government pays each state a certain percentage of the cost of care for anyone eligible for the health coverage. As a result, the more money states spend on Medicaid, the more they get from Washington.

Under the approved demonstration, CMS will work with Tennessee to set spending targets that will increase at a fixed amount each year. The plan includes a “safety valve” to increase federal funding due to unexpected increases in enrollment.

“The safety valve will maintain Tennessee’s commitment to enroll all eligible Tennesseans with no reduction in today’s benefits for beneficiaries,” CMS said in a statement.

Tennessee has committed to maintaining coverage for eligible beneficiaries and existing services. In exchange for taking on this financing approach, the state will receive a range of operating flexibilities from the federal government, as well as up to 55% of the savings generated on an annual basis when spending falls below the aggregate spending cap and the state meets certain quality targets, yet to be determined.

The state can spend that money on various health programs for residents, including areas that Medicaid funding typically doesn’t cover, such as improving transportation and education and employment services for enrollees.

The 10-year waiver is unusual, but the Trump administration has approved such long-term experiments in recent years to give states more flexibility. Tennessee is one of 12 states that have not approved expanding Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, leaving tens of thousands of working adults without health insurance.

“The block grant is just another example of putting politics ahead of health care during this pandemic,” said Johnson of the Tennessee Justice Center. “Now is absolutely not the time to waste our energy and resources limiting who can access health care.”

State officials applauded the approval.

“It’s a legacy accomplishment,” said Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee, a Republican. “This new flexibility means we can work toward improving maternal health coverage and clearing the waiting list for developmentally disabled.”

“This means we will be able to make additional investments in TennCare without reduction in services and provider cuts.”

This story also ran in KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation) that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Comments are closed.