‘What He Loved Hurt Him’: Mom Discusses Youth Concussion Risks After Losing Son

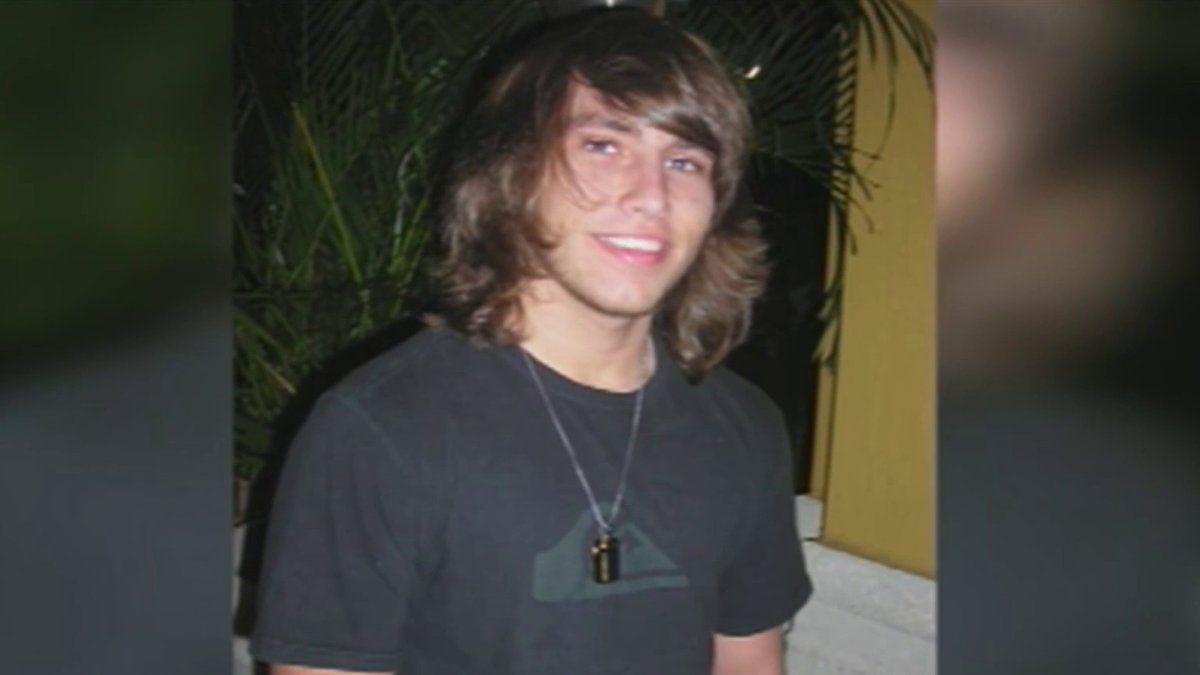

A South Florida mother, Diana Colon, is sharing her heartbreaking story to raise awareness about the risks young athletes face from repeated head injuries. Her 16-year-old son, Daniel Brett, tragically took his own life in March 2011 after suffering multiple concussions while playing football. For Colon, these injuries became personal, and now she’s determined to educate others about the dangers of contact sports and brain trauma in young athletes.

A Mother’s Pain: The Loss of Her Son

Daniel Brett began playing football at the age of 11, developing a deep passion for the sport. He dreamed of playing for the University of Miami and worked hard to secure a spot on the junior varsity football team at Cypress Bay High School. However, during a practice session, Daniel showed signs that something was wrong—he stumbled and admitted to his coach, “I can’t see.” It was the beginning of a downhill spiral for Daniel, who never played football again after that incident.

Following the injury, Daniel began suffering from severe migraines and depression. His mother recalls how he changed drastically, explaining, “He stopped being the Daniel that I recognized, that our family loved.” What the family didn’t realize at the time was that Daniel had sustained a brain injury. They sought help, but the damage had already been done.

Understanding the Risks: Research on Concussions and CTE

In recent years, researchers have made significant advancements in understanding the risks young athletes face when exposed to repetitive head impacts. Boston University’s CTE Center, which studies Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), published a study highlighting the dangers. The study found that among 152 young athletes who died before the age of 30, more than 41% showed evidence of CTE, a degenerative brain disease linked to repeated head trauma.

Diana Colon now understands that it’s not just the major concussions that are dangerous, but the cumulative effect of repeated sub-concussive hits. “Over time, these small hits damage the brain,” she explained. This cumulative damage is what researchers believe may have contributed to Daniel’s struggles and ultimate death.

Dr. Daniel Daneshvar, an expert at Harvard Medical School and the CTE Center, explained that repeated concussions, such as those suffered by athletes like Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovailoa, have a progressive effect on the brain. (https://crystalbaypoolsva.com) “After multiple injuries, it takes less and less force to cause problems later,” Daneshvar said, underscoring how fragile the brain becomes after repeated trauma.

A Call for Change: Delay Contact Sports for Young Athletes

Since her son’s death, Colon has taken an active role in raising awareness about the dangers of contact sports. She donated Daniel’s brain for CTE research, and doctors discovered proteins linked to the brain disorder. The findings reinforce the importance of protecting young athletes from repetitive head injuries.

The study by CTE researchers concludes that children should not start playing contact sports involving head impacts until they are at least 14 years old. Colon hopes her story will encourage parents, coaches, and medical professionals to take concussions seriously and protect young athletes from the long-term consequences of brain trauma. “What he loved hurt him and ended up taking his life,” Colon said. “It shouldn’t happen to anybody.”

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.